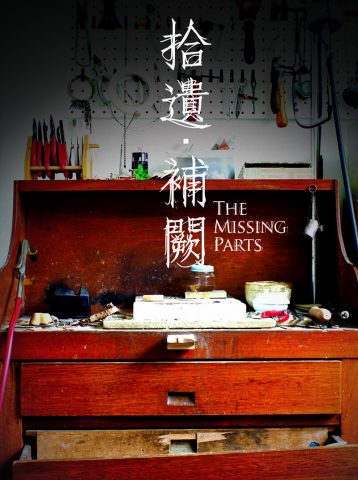

Clasp

Ever since I was small, I have always liked to collect small and odd objects. I got them mostly from second-hand shops, flea markets, and sometimes from friends. I am always fascinated by their connections to the past. I would imagine what had happened to these objects, and let my mind roam freely. I am not a true collector though, as I quite often would dream up ways of infusing new life into them. Time lay traces of history on old objects, and to me, they are much more approachable than new items.

A few months ago, I re-discovered a little mesh bag that I have almost forgotten about. I found it at a flea market in Paris many years ago. It is about seven centimetres tall and not quite five centimetres wide. Its clasp at the opening has long fallen off, and a dot of solder is all is left. I bought it originally for its exquisiteness. After some background research, this bag is likely to be for loose coins, and this kind of mesh can have its root traced back to the Middle Ages, where knights would wear metal mesh for protective use. The making of this type of clothing, called mail or chain-mail, was very labour intensive. A good quality one could be consisted of 250,000 individual iron rings. I feel a little bit more connected to the people of that era. The bag I have was machine-made, and apparently was very popular earlier last century. The mesh-making machine was only invented in 1909. All of a sudden, my thoughts started to wander.

Is this broken bag still useful? The rings forming the mesh are all intact, and the overall proportion of the bag itself is tasteful. It is only missing a clasp. For a jewellery piece, the usual consideration would be on its aesthetic. We praise a bracelet as being “beautiful”, but rarely would we proudly proclaim it “practical”. But for this small component – clasp, it always has to be pragmatic. This is the most basic, and the purest, and often the most overlooked component.

I still remember the times when I was studying fashion design. My teacher would passionately explain, how to properly prepare and attach buttons and catches. These should never be afterthoughts, but should be an integral part of the original design. Orientation of the fabric should be taken into account, plus interfacing should be added when necessary. Each and every tiny steps should be performed meticulously. A properly designed and attached button, she said, should last the lifetime of the clothing. This level of dedication burned an everlasting impression on me.

Being a jeweller, it automatically means friends and relatives would bring in their damaged jewellery pieces and ask for advise. More often than not, the damage area is around the clasp. I still remember a rather thick necklace that I used to have as a child. It had a well-proportioned M-clasp, in which a piece of jade would hang. I was a naughty child, but this necklace survived all my tricks. Today’s designs, however, usually use too thin a chain, and let the pendant freely slides. Over time, damage is almost inevitable.

From the basic theory of jewellery-making, a clasp should be reliable, comfortable and easy to use. I once made a leather bag for a family member. I only wanted the best, the most sturdy, and the most reliable. I first observed his habits and routines, and designed the bag around his needs. The strap of the bag was made with his height in mind. All the details and colors were carefully finalized. The outcome was a classy and handsome bag, made from solid tan cowhide, with soft sheep skin for backing. Of cause it was all hand-made, down to the last stitch. I even made the clasp from a single piece of 3mm thick sterling silver sheet, stamped with the intended owner’s initials. It was the best leather piece that had I ever made, and I was happy. All these well intentions resulted in one comment: It was too heavy. It made me realized that in life, we are not always searching for the best, but the most suitable or appropriate.

My husband does not like to see things going wasted. He is the official repairman of our home, and will save up all spare parts, raw materials in his little treasure box for later use. Every time his “treasures” find new lives in a repair, the glow of happiness on his face is so sincere. A few years ago, he took a small piece of brass from his treasure box, and made a rest for my blowtorch. It was a simple hook, but the design and placement took into account my habit and the nature of my work, and also the functional requirements of the torch. When I now casually put down my torch, I still feel the comfort of the alignment between the body, the tool, and the work at hand.

Reliability, comfort, and ease of use are the basic requirements for a clasp. Extending these to our approach to daily living would mean a relationship of moderation and appropriateness with out surroundings. It is simple, unassuming, and timeless. I really have to thank this little mesh bag for giving me a chance to reflect on our modern ways of living.

釦

從小便喜歡收藏零碎細小的物件,它們總引起我的好奇心和思考。為親近它們多一點,我會對它們作一定的探究,思緒跟隨這些小物件游走,樂趣無窮。收藏基於一種對物件多一點的了解,然而有時也會把收藏的舊物改頭換面,令它們變成另一種有用的樣式。二手店、各種市集都是我的尋寳地。當中所尋獲的舊物有一份自身的歷史痕跡,它們比新的物件總是多了一分隨和及不經意地流露出的一點靈氣。

今次碰到的是一個闊不足五厘米,而長約七厘米的小小金屬網袋,開口上的釦已經掉了,只餘下一點焊接的痕跡。它是我多年前遊法國時在跳蚤市場找到的,數月前清理貯物柜時,又和它再遇。起初只感覺它精巧,後得知少許歷史背境,知它應是一個以金屬網製的零錢包,這種金屬網起源於中世紀的歐洲,為武士的保護甲,每件可用上二十五萬個人手製作的小圈子連繫而成。看到這個零錢包一下子好像跟那時代、那地方的人有了深刻的了解;手頭上這一個是用織網機製作的,為當年非常流行的款式,相對於中世紀的手製金屬網,這種織網機卻遲至一九零九年才出現。在把玩間我一度在這段長長的歲月中徘徊、沈思。

在這錢包上,金屬小環連連相接,比例均勻,造型大方,少了的只是一雙釦,頓使它欠缺了功用的本質,看起來倒像是一件精緻的首飾;想一想首飾在定位上多被列入裝飾性,製作上考慮的多在於美觀,因此在首飾中多見到美麗的手鏈,而少聽到多實用的手鏈,事實上釦這小零件是帶有實用性的,給人的印象是平實、純粹,但這也是使人們常漏了眼的地方。

還記得多年前讀時裝設計時,老師鄭重地講解,如何把鈕和釦結實地釘在衣服上是縫製衣服的最後階段,絶不能草草了事,從一開始製作就需要精心計劃,依從布料的縱橫紋理垂直剪裁,在布下還需要貼上襯裡令其更結實;當中起針、回針及打結,一絲也不可以馬虎,再配上合宜的鈕釦,所造的衣服穿上多年也不需要補縫。由小小的鈕釦處理態度,體現出發自心靈誠實的巧手精神,實在叫人敬佩;所以對於老師悉心的教導,我一直銘記於心。

多年來從事首飾製作,因為工作關係常有親友拿破損首飾給我作修補,破損形式不外乎掉釦斷鍊等。回想兒時常戴着一條粗銀鍊,正前面有一個大小適中,粗瘦合理的M式釦子,懸吊玉垂飾於正中,任由小淘氣有多搞鬼也少有損毀。反之時下的鍊、釦與垂飾在不合比例的並置下組合,加上垂飾自由的懸繫,漫不經意的破損實在難免。

首飾的基本理論已指出,釦除了可靠實用還要舒適、易用。有一次造了一個皮袋給家人,一心要造一個最好、最結實耐用的。首先硏究他的生活習慣,如每日上班的裝備,一一記錄,以為皮袋的間格和型狀設計草圖,又計算他的高度以定立背帶的長度,還因應他的喜好選擇顏色和其他細節,最後根據這些記錄造了一個以結實棕色牛革佩以淺棕色小羊皮托裡,間格齊全,款式典雅,手工精緻的皮袋,還在它的背帶上加上一個以三毫米原件白銀手鋸成形的釦子。釦上刻上物主名字的字首,滿以為完美無缺,但這一切經精心計算,將最好的加起來的結果是──太重。由此我所得的結論︰凡事不是要求最好,而是最合適。除了釦子外,日常用品也應有以上「以人為本」的精神吧。

外子是一個惜物的人,所有家中破損的物件也是他一手修理,他還會從破敗的物件上把未耗損的零件拆下來,收藏在他的寶物箱中,等待下次有用得着它們的時刻;每次遇到他的寶貝藏品有毛病時,這些零件,就發揮了使器物重生的功用,這時的他,面上流出沾沾自喜的神情,是多麽的真和善。細數之下,發現家中有很多出自他雙手的作品;多年前他在寶物箱找了一小塊黃銅片,為我的打金工作枱上的燈吹加了掛鉤。此鉤依黃銅片的大小,物盡其用,加以剪裁、成形,因應燈吹的功能和我工作的習慣和需要而製定、安置;隨手釦上燈吹,切身體會一種人、工作、工具連成一體的舒服。

釦的基本要求,是可靠、耐用、舒適和簡易操作;推而廣之是一種平實、適中和物我兩忘的關係,簡單樸素而恆久。還要多得這個小網袋,令我得以在這追新棄舊的生活中有一點反思。